There's Something About Murakami

In honour of the upcoming Powell Street Festival, I had the chance to chat with Jay Rubin and Ted Goossen, two well-known translators of acclaimed Japanese author Haruki Murakami. We talked about the pressures of being a translator, how much can get lost in translation, their favourite Murakami novel, and more.

When we’re reading a translated work, how much are we reading the author and how much are we reading the translator?

Jay Rubin: This is one of those eternal questions that will never be resolved. In terms of the words on the page, you are reading the translator 100%. The translator never would have put those words on the page, however, if the author hadn’t written the work. How much of that work actually makes it to the page, though, is a slippery business. Some translators think of themselves as perfectly transparent media, which is a pleasant delusion, especially when it comes to traversing the distance between languages as different as Japanese and English. If the translator doesn’t think and interpret every step of the way, you’re going to end up with mush.

Ted Goossen: Around 8 or 9 years ago I was invited to a symposium in Japan with over 30 translators of Murakami from around the world, and I remember thinking there has to be a range of translating ability here, and yet, Murakami is popular virtually everywhere- there’s something about Murakami that seems to get across no matter who is translating. Also, the fact that you’re translating one of the great storytellers of our age is a tremendous boon for translators and probably covers up for deficiencies that we may have in our skill.

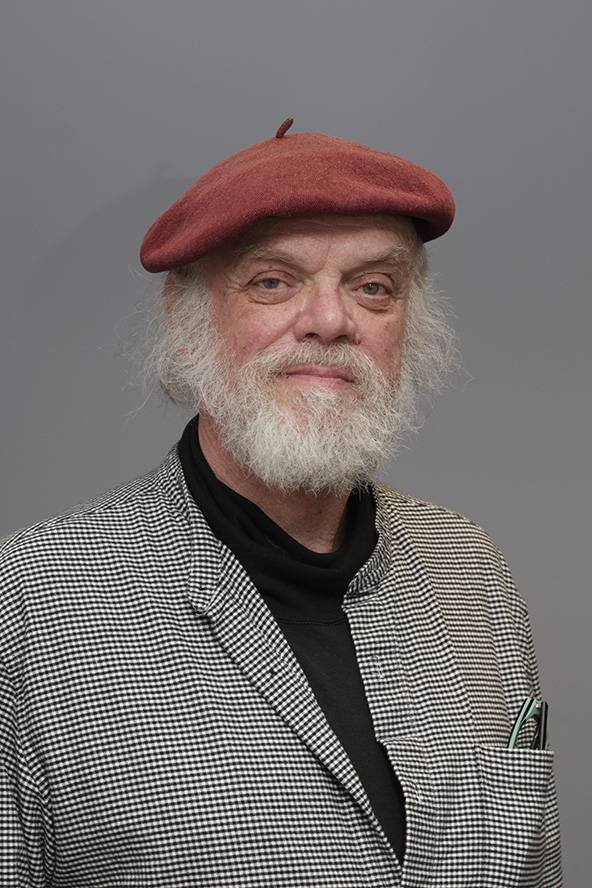

Jay Rubin and Haruki Murakami

What have you translated by Haruki Murakami?

Jay: Of his novels I’ve translated The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Norwegian Wood, after the quake, After Dark, 1Q84 Vols. 1 & 2, and Absolutely on Music. I’ve also done a bunch of his stories, mostly for The New Yorker and reprinted in The Elephant Vanishes and Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman, plus the hard-to-find “Good News and Other Stories” in Southward (December 2006) and Hayden’s Ferry Review (Spring/Summer 2012). I also translated his Jerusalem Prize speech “Of Walls and Eggs”.

Ted: I’ve translated a number of his short stories that will be coming out in a new collection called Men without Women, his first two novellas which were re-released as Wind/Pinball, and presently I’m working on Killing Commendatore with Phil Gabriel. I’ve also worked with Phil on Novelist As A Vocation, which is expected to come out in a year or so. Besides that, I’ve translated a number of his essays, including the one accompanying his Japanese translation of The Great Gatsby.

What is your all-time favorite Murakami novel?

Jay: Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. It’s probably the most perfectly-formed, imaginative representation of Murakami’s world.

Ted: Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. I read it when it first came out, when I was young and living in Tokyo, and it just bowled me over. I loved it so much I got depressed when I finished because I wanted to keep on reading, and it kind of pointed me in a new direction in my work and my interests.

Translator Ted Goossen.

Which is more challenging- translating Japanese into English or translating English into Japanese?

Jay: I don’t have enough literary command of Japanese to translate into it. I just published a book of essays in Japanese last year, and that was tough enough! In general, I think people ought to translate into their native language.

Ted: I can’t translate English into Japanese. No way! My Japanese isn’t that good, and generally speaking, I think it’s more difficult by far to translate into your second language (Japanese). When you translate into your first language (English), it’s a very natural thing. You’re interpreting or channelling rhythms and voices that you feel deeply, that are connected to your childhood and everything else, and it’s just not the same if you’re trying to translate into your second language.

How do you approach culturally specific idioms and figures of speech?

Jay: My main “approach” is to run away—to not translate writers who use culture-specific idioms and figures of speech. Murakami presents very few such problems. There is virtually nothing in Japanese that can be translated literally into English. Even the most ordinary expressions are weird and interesting: arigatō, konnichi wa, ikimashō are nothing at all like “thank you,” “hello/good day,” “let’s go.” We just use those as functional equivalents.

Ted: It’s difficult, but we try to come up with creative solutions such as finding English idioms that are somehow comparable to the Japanese ones. We may sometimes attempt to appropriate some aspect of the Japanese and translate that and include it in a kind of newly constructed idiom but that’s very tricky and it usually doesn’t work. I think all of us try to do that more in the beginning than once we’ve been translating for a while.

**edited for length and clarity

Photo courtesy of u/Brawl888.